As Ian Isherwood explained in his reflection on our trip, when we embarked on that plane to France on the 18th, we had a precise image in our minds of what we hoped to do in Le Verguier. We had spent months – some of us years – in planning a way to properly memorialize the incredible stand made by Jack Peirs and the 8th Queen’s during the first few days of the German Spring Offensive of 1918. We knew we wanted to stand on the very ground that Jack and his men had defended a century earlier and we knew that we wanted to share this experience with our followers back home, using video to interact across continents. We also hoped to have the opportunity to see the bells in the church at Le Verguier, which were erected in the 1920s as the town attempted to rebuild and for which Jack’s division, the 24th British Division, had raised money in the years following the war as a way to honor their comrades who had fallen in the defense of the town.

My role on this trip was to secure us the opportunity to see those bells. I am the only French speaker on #teampeirs and it fell to me to make the necessary communications with the Mayor of Le Verguier, Abdel Boudjemline. A few weeks before we were to head to France, I had contacted him to see if we could have access to the town church. Luckily, the mayor responded that he was more than happy to let us into the church and guide us up to the bells. Though we were thrilled to have the opportunity to see the memorial, we had no real idea of what our time in the town would be like. We blocked out a few hours in our schedule on the afternoon of the 21st to explore the church and hoped that the bells would live up to our expectations.

We were all nervous to meet with the mayor, I doubly so because I had to be the translator for the group. I did not really know what we were walking into – all I knew was that we were going to be let into the church – and I certainly did not know whether or not my French could stand up to such a pivotal moment in our trip. I had studied abroad in France before and spoken the language extensively during that time, but I had never before been relied upon so heavily for my language skills. To keep this story as brief as I can, I’ll simply say that I was feeling a good deal of pressure to make sure that our meeting with the mayor went well for us as historians, but also as Americans trying to make a good impression abroad. Luckily, it turns out that my fears were unfounded and, like much of our trip, our meeting in Le Verguier went better than we had dreamed it would.

When we first walked into the town’s small municipal building, we were greeted by not only the mayor of the town, but also by his deputy and a journalist for a regional newspaper. They ushered us into a meeting room where they had laid out an incredible spread of French pastries for us. They brewed us hot, fresh coffee, which was extremely welcome after a long, cold day walking the battlefields. Shortly after we arrived, we were joined by two more Frenchmen: Philippe and Henri Séverin, the grandson and great-grandson of Charles Séverin, who was the mayor of Le Verguier in the 1920s and a veteran of la Grande Guerre. He had corresponded with Jack after the war; Jack had wanted information on the location of his old dugout, and Charles Séverin drew him a map of its location and sent along photographs. Philippe and Henri were just as willing to help us as their ancestor Charles was to help Jack. They shared with us their passion for the history of their town and their family, dashing back and forth from their homes to the municipal building with their hands full of old documents from the era – including the Croix de Guerre that the town had been awarded – and photocopying anything and everything they thought we might find useful. We were completely taken aback by their incredible generosity.

Later that afternoon, the Mayor took us to see the church. I won’t soon forget how nervous he was to take us up to see the bells; he kept telling us to be careful and insisted upon going first up the spiral staircase to the belfry, pushing past cobwebs and up rickety wooden stairs. He stopped every so often to make sure everyone was safe. It wasn’t a long way up, but for decades, the only person who went up to the belfry was the man who serviced the bells. We eventually made it all the way up to a dark little room, filled with dust and with very little standing room, where we could see the bells.

As we stood underneath them in the shadows, seeing in person the memorial to the fallen of the 24th Division that Jack and his men had worked so hard to raise money for, I found that I had tears in my eyes. It felt like we had, in some small way, paid our respects to Jack and his men. Although we had so much left to accomplish on our trip, in that one moment, it felt like we truly done our duty to Jack. And when we eventually descended and stood outside of the church by the town memorial to those lost in WWI, the bells began to ring. For a moment, it quite honestly seemed like the world stopped, like we were reaching across the boundary of time to experience what the 24th Division experienced when they came to dedicate the memorial in 1926.

When we retired that day, I thought we had experienced the best of what we would experience on that trip. But then, the next morning, we arrived into town to see the French flag flying atop the memorial to the 24th Division; the people of Le Verguier had put their colors out for us. It was an overwhelming and incredibly moving show of international friendship. I still do not have the words to describe how it felt to see that flag rippling in the wind.

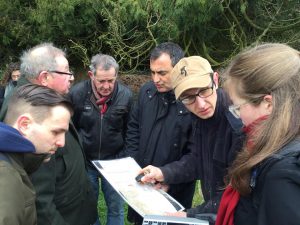

From there, we went with the same delegation of Frenchmen in search of Jack’s dugout. We stood in wet fields and studied the letters and photographs from the collection with the descendants of the man who sent them to Jack. As we tramped through the fields, the Mayor called the owners of the land to ask them if they had ever heard or seen anything that might suggest the specific location of Jack’s dugout. We had what felt like the entire town of Le Verguier with us in search of Jack at the very moment when, one hundred years ago, he ordered the battalion papers burned and prepared to retreat after a long night of defending the village. And we think we found him.

The term “world war” has a new meaning to me after working with our friends from Le Verguier. I saw what it meant to them to have us there, paying homage to their village, and I know what it meant to our team to have received such a kind welcome from them. I do not exaggerate when I say that we would not have found Jack’s dugout without them. International cooperation led us to him. And although I do not pretend to liken our experience to Jack’s, I can say that thanks to the people of Le Verguier, I know what it is to have allies in a great historical endeavor.

It is a powerful thing to reconstruct the history of a war that consumed the world. That we did it with our friends from Le Verguier seemed not only appropriate, but entirely necessary.