In order to help visualize the action on the ground during the German Spring Offensive, #teampeirs has been creating maps to pinpoint key positions during the assault on March 21-22, 1918. By using the ArcGIS software package, we can take scanned maps and overlay them on a modern map, and then annotate them in various ways.

Update, March 22, 2018

One of the advantages of using digital maps is that we can update them based on new research findings; for example, the team in France located the Battalion HQ dugout, so we’ve updated the location of it on the maps. It happened to be in a private yard that we didn’t have access to and was overgrown, so it wasn’t going to be something we could find from a modern satellite map, and was really only discoverable through the help of locals. The HQ location happens to correspond to a large dark blob on the 1919 map, but without context or a legend, assuming that was the dugout would have been just a guess without being there. Building digital maps certainly benefits from a variety of perspectives.

Finding Trench Maps

Using trench maps from the McMaster University Library trench map collection, we discovered 4 trench maps that would support research done on the ground, as well as create annotated digital versions. All of these maps are licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-2.5 CA license.

Le Verguier lies in the southeast corner of 62c.NE, so to get a more complete understanding of the area, we would need to use all four maps.

Overlaying Maps

Overlaying a historical map on top of a modern one requires a fairly accurate map image, and the trench maps work well since they were created by experienced cartographers (and had to be accurate in order to support calling in artillery strikes). These maps line up well with a modern satellite image. Through a process called georectification, we can take points that exist on a historical map and match them up with points on a modern map. Then ArcGIS will warp and stretch the historical map to match the modern one as best it can. When presented with an accurate historical map, the process is less difficult, since the software doesn’t have to do as much. One of the challenges of georectification is finding control points on each map that correspond to each other. This part of France has not been urbanized in the last century, so many of the streets and other infrastructure line up with little effort. What was most beneficial, however, was using natural elements, such as small copses of trees that haven’t grown past their boundaries in 100 years, to serve as control points. So, essentially, we could mark out a small copse on the historical map, and do the same on the modern map, and the software would rectify the scanned image to get things to line up.

Four Trench Maps Overlaid on a Modern Satellite Image

For the purposes of illustration, here are our 4 trench maps, cropped a bit, and marked out with rectangles to show the boundaries of each map (if the trench maps do not appear, zoom in with the +).

Overlaying a Hand-Drawn Map

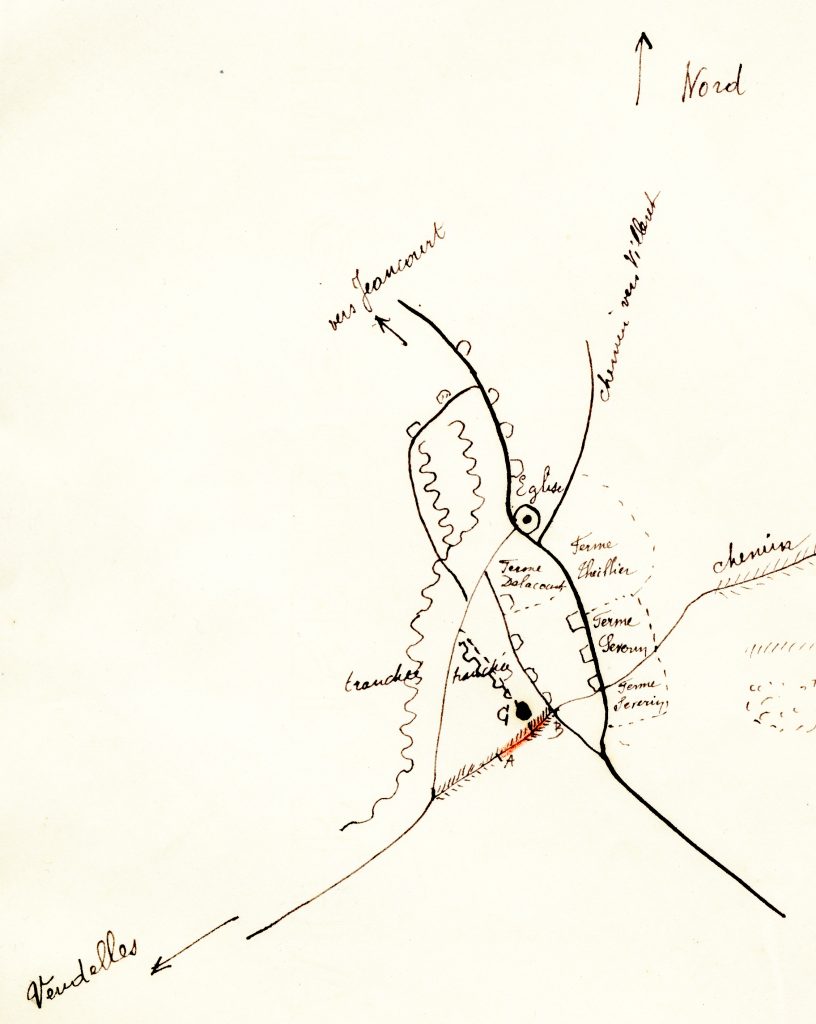

Because of their accuracy and consistency, working with the trench maps wasn’t too difficult. Somewhat more complicated was georectifying another map we have in our possession, a 1919 hand-drawn map of Le Verguier by its then-mayor, Charles Severin.

This map had to be rotated and stretched a bit to get it to correspond with a modern map, and even then, it’s not perfect. However, it’s pretty close, and for a hand-drawn map, about as accurate as you could be without more advanced training and tools.

Annotating the Maps

Once the maps are georectified and overlaid on a modern map, we can then add an additional layer that can pinpoint different locations on the map. All put together, they can be used to locate historical locations on a modern map. Our final map contains the 4 trench maps, the hand-drawn map, and the annotated points. By loading this map with a mobile phone with GPS enabled, you can pinpoint your location in relation to the other points, using it as a tool to find your location relative to the historical sites (if the trench maps do not appear, zoom in with the +).

Final Map, with Trenches, Hand-Drawn Map, and Annotations

If the trench maps do not appear, zoom in with the +.

This map primarily serves as a tool for analyzing the situation on the ground. By using the ability to measure distance, we were able to determine the location of a ridge identified in the 8th Queens Diary; this ridge was occupied by the 8th Queens at some point on March 22, 1918. However, the official diary claims this was 600 yards west of Le Verguier, while it is more likely, based both on topography and movement, it was 600 yards west of Vendelles.

Creating a Tour of March 21-22, 1918

These maps tell stories, but without additional context, they require supplementary materials to negotiation. However, we can also use these maps with a different tool, ArcGIS Story Map Tour, to create a time-based map that gives us the sequence of the actions of March 21-22, 1918. Using the 8th Queens Diary, we can match location with time and action, creating a virtual location-based timeline that combines modern and historical.

Paper Maps, Digital Tools, Lessons Learned

Building these digital maps has been a long process; not only was learning the technology a bit of a slog, but reading a trench map isn’t exactly easy either. However, with practice, things become easier, and we can provide tools for everyone not on the ground in France to follow along on the path of Jack and the 8th Queens. We can take the lessons learned from building these maps and create more annotated trench maps as well, allowing them to be tools for students and educators as part of studying the Great War.

The trench maps themselves are testaments to the ability of the cartographers to create accurate maps. But there is also an unexpected element that has come through analyzing these maps in relation to modern ones: the relative unchanging-ness of the French countryside, 100 years after the war. Streets and buildings were rebuilt from their foundations, the boundaries of farms and copses of trees remain relatively the same, at least in this part of France. The scars of the war are carved onto the very land, and while there has been overgrowth and return of life, they are still there, sometimes just inches below the surface. There is something here to be said about the resilience of the human condition, yet a sadness as well, as it may not be long before those who live in these small rural enclaves will no longer be around to memorialize those who fought and fell there.

Using the tools and methods afforded to us by Digital Humanities, we have been able to bring history to life, taking our readers into the shoes of a soldier and humanizing the events of a dehumanizing war. Maps are a powerful way to orient historians and their audiences towards an understanding of how history has been perceived and lived out; our human experience is bound by time and space and our continued movement through both. It’s been exciting to show not only the trench maps, such as the one Jack carried that is in our possession, and see the reactions from students to them, but also the digital versions and how they help them make sense of it all.

Thanks to all who have supported #teampeirs!

Excellent work. It helps clarify the days immediately prior to when my grandfather, CQMS Walter Hitchcock, was hit in the leg on 27 March and taken prisoner.