Transcription

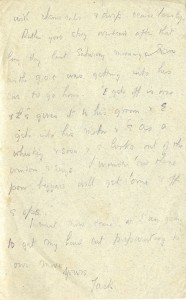

21.9.15

(Rec’d 3 Oct 15)

My dear Family,

I hope this finds you as it leaves me at present.

Am looking forward to a new billet as am under orders to move to night & you must guess the place, as I can hardly tell you its name, but it is about 10 miles from here. As we are moving we have had no mail, but should get one when we reach the new place. There were tremendous rumours that we were through the Dardanelles yesterday but they are probably not true. However as they arose from the local postman they may not be so incorrect as usual. The CO has gone ahead to-day to spy out the country, but will be back to-night or we shall meet him on the way.

They had a respirator test here the other day when one of these Staff people came along with a cylinder of Bosch gas & filled a trench with it & then people walked through it & came out coughing & spitting but all safe. The respirator is just like a sack to fit over the head & neck & fitted with a piece of talc to look through. The talc has a habit of splitting & letting the gas in. Then of course the thing is of no use. You feel nearly suffocated when you put the thing on but some get used to it. They also give us a 2nd kind to use in addition which is merely a pad to put over your mouth & nose.

I believe that eventually they are going to serve out a thing which is good against every sort of stink known or unknown, but it has not arrived yet. I have just given my tunic to my servant to sew a pocket on the inside to keep these things in as they are both saturated with chemicals & drip ceaselessly.

Rather good story overheard after that long day last Saturday morning. As the G.O.C. was getting into his car to go home, “E gets off his orse & gives it to his groom & E gets into his motor & E as a whiskey & soda & E looks out of the window & says I wonder ‘ow these poor beggars will get ‘ome & off E ops.

I must now cease as I am going to get my hair cut preparatory to our move.

Yours,

Jack.

Commentary

After training for most of September in comfortable countryside billets, the 8th Queen’s were on the move. Though Peirs was conscious of the need to keep mum to his family about their movements, here he is specific enough that if they were following the newspapers (and they were) and had a decent map of France, they would be able to guess that he was on his way to the British front lines, to the east towards Vermelles.

As part of their final training before moving to the front, the men of his battalion were introduced to poison gas from a captured German cylinder that was frighteningly opened in a training trench. Peirs and his men had to walk through the trench wearing their new respirators to get used to the feeling of an actual gas attack.

one of these Staff people came along with a cylinder of Bosch gas & filled a trench with it & then people walked through it & came out coughing & spitting but all safe.

The chemical industries of Britain and Germany both mobilized during the war to create lethal gasses. The German Army introduced poison gas on a wide scale at Ypres in April 1915. Seven months after the first attack, countermeasures were in place to minimize casualties from gas so that British soldiers could continue to fight in a toxic landscape. The British Army had developed their own gas specialists and were learning to use gas, which Robert Graves wrote was referred to as “the accessory” in 1915. The British Army was essentially learning how to adapt to the new weapon (and use it) on the job.

The respirator is just like a sack to fit over the head & neck & fitted with a piece of talc to look through. The talc has a habit of splitting & letting the gas in.

Though the new respirators were seen as an improvement, they were crude and unreliable, disliked from the moment they came out of their crates and were issued to the men. Peirs found them a smelly but necessary nuisance. You can feel the disdain of having to ask his servant to sew pockets inside of his bespoke uniform to carry such a contraption.

At the end of the letter, Peirs relays a humorous anecdote overheard from one of his men about the General Officer Commanding XI Corps, General Sir Richard Haking.

As the G.O.C. was getting into his car to go home, “E gets off his orse & gives it to his groom & E gets into his motor & E as a whiskey & soda & E looks out of the window & says I wonder ‘ow these poor beggars will get ‘ome & off E ops.

Note that Peirs is poking fun at Haking’s obtuseness through the dialect of a working class Tommy. Peirs relays their story through his own eyes – a middle class solicitor – who was clearly amused at the types of things his men found funny as well as the ways that they put things. Perhaps it was easier for him to poke fun at the general’s aristocratic obliviousness through their eyes than his own.