Transcription

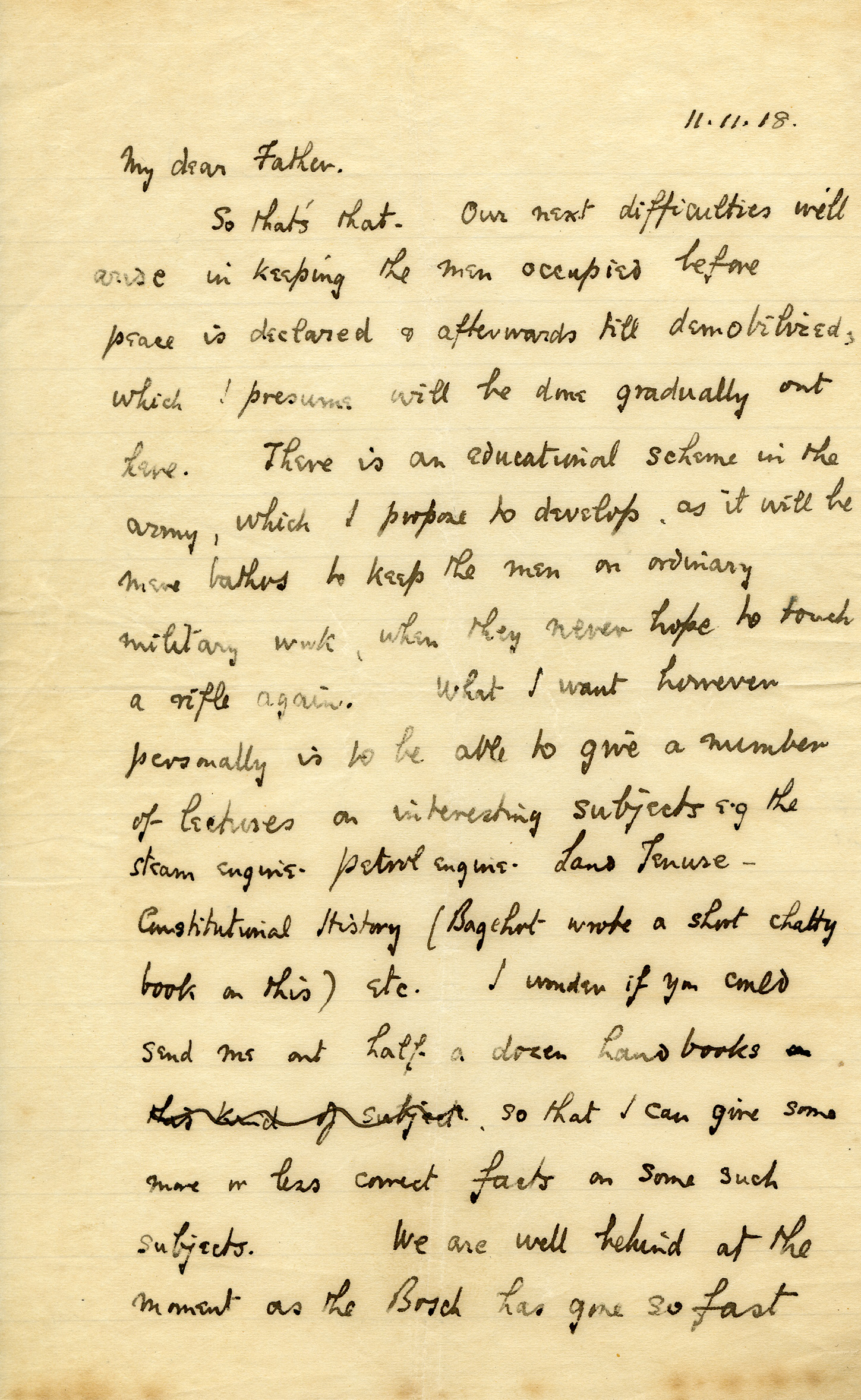

11. 11. 18.

My dear Father,

So that’s that. Our next difficulties will arise in keeping the men occupied before peace is declared & afterwards till demobilized, which I presume will be done gradually out here. There is an educational scheme in the army, which I propose to develop, as it will be mere bathos to keep the men on ordinary military work, when they never hope to touch a rifle again. What I want however personally is to be able to give a number of lectures on interesting subjects e.g the steam engine, petrol engine, Land Tenure, Constitutional History (Bagehot wrote a short chatty book on this) etc. I wonder if you could send me out half a dozen handbooks on this kind of subject, so that I can give some more or less correct facts on some such subjects. We are well behind at the moment as the Bosch has gone so fast

[page]

but I doubt if we stay here, as we are crowded in with a lot of civilians & the men have none too much room to themselves. The Division has got a very good chit from the Corps Commander, & I think they put up a very good show in the beastliest conditions of weather. I hope to get some leave at the end of the month & look forward to see you.

Yours

Jack.

Commentary

With that being that the war was over for Peirs and his men. The survivors of 8th Queen’s returned home as demobilized veterans of the Great War for Civilization in 1919. There was reason to be hopeful in the silence that befell them, especially after the last week of fighting it out against a weakened, but still resilient, enemy.

Some, like Peirs, went home to successful lives in peace, resuming where they left off. Others, though, struggled and bore both the physical and mental scars of their wartime service in all-too-apparent ways. All wars affect people differently, of course. No doubt for the men of the 8th Queen’s the moment of the armistice came with a sense of weary relief, as well as, complicated feelings of trepidation about what would happen next.

The war never left them, of course. It was the binding moment of their generation, one that also shadowed their adulthood. Peirs’s beloved ‘lambs’ came back to a Britain in which the war’s memory was contested in the decades of their adulthood.

Collectively, in Britain the initial celebration of allied victory in 1918 turned to a general sense of deep mourning in the early 1920s. Survivors had to emotionally adjust to peace and learn how to appropriately mourn their comrades. In the 1930s, the world turned dark again; the rise of fascism made a mockery of the sincere beliefs many held that the sacrifice made during the war would end all future wars.

Of course, many of their comrades never had the ability to debate the war’s meaning and its memory. The war’s greatest imprint was its scarring and the failure of the deep wounds scourged upon the social fabric of the nation to ever really heal.

The 8th Queen’s lost 505 men in their three years of service. Some of these men have known graves, but many do not. Each man came from somewhere and most, we can presume, had families – hundreds of families whose lives were forever worse for the war. For them the war would never end and its enduring legacy was the memory of the son or brother or nephew who was once alive, but now lay dead in a foreign field and only possibly with a known grave.

Peirs knew this undersized battalion of dead men. He knew them by their names, by their voices, and by their gaits and mannerisms. He watched as they trained in England in 1915 – naive men and boys getting ready to go to war. He commanded them at Loos, the Somme, and Ypres as their learned to fight – as they suffered and bled – and he was near many of them when they were killed. Peirs lived knowing that the decisions he made as their officer contributed, in some way, to their fate. Such is the burden of command.

It’s no wonder that there is no joy or celebration in this letter. There is a sense of resignation and then a desire to move beyond, to think ahead to helping his men, to keep their minds off what they had just gone through and occupied until they could go home. To Peirs that indeed was that – the armistice an ending to an hard job that he believed had to be done – a job that he and his surviving men, we should remind ourselves, did until the bitter end.