Ninety-nine years ago yesterday – March 21, 1918 – was an important date for many veterans of the British Army in the First World War. The first phase of the German Spring Offensive(s), Operation Michael, began that day with an attack on General Hubert Gough’s Fifth Army. The German attack was well-planned and overwhelming: 8,000 artillery pieces opened up on British lines dropping a million shells on unfortunate men of the BEF. Covered by fog, German assault parties advanced across no man’s land and shattered sections of the old British front line.

In the midst of this chaos were the men of the 8th Queen’s and their commander, Lt. Col. Jack Peirs, D.S.O. The 8th Queen’s was positioned at Le Verguier, a small French village surrounded by rolling farmland, a place that was right at the heart of the German offensive. The 8th Queen’s and the 17th Infantry Brigade (24th Division) manned trenches at strong points covering roads and the approaches to the village. When Germans began their attacks on the morning of the 21st, Jack’s men were ready to resist them as best they could.

Interestingly, Jack Peirs was four miles behind the front lines when the Germans attacked. A few days before, Peirs had injured his foot, and the wound had turned septic. The battalion medical officer, Captain C.J. Lodge Patch, recommended rest and so Peirs was in a billet to the west with the baggage and transportation animals when his men came under attack. Leaving his bed, Peirs rushed to the front (as best he could rush on his poisoned foot) and arrived to find his men fighting hard but holding their positions.

At Le Verguier, Peirs’s presence inspired his men to resist. He personally organized and led several counter-attacks at moments when it seemed like their positions might be overwhelmed. His men performed well and Peirs continued to be a calming presence. But as the day progressed into night, Le Verguier went from being a salient thorn in the side of the approaching Germans, to being an untenable position that was nearly surrounded. On the 22nd, Peirs ordered the battalion papers burned and that morning he withdrew the remnants of his battalion westward, joining the thousands of other British soldiers on the move. Still, the battalion had held and delayed the German advance in their sector for over twenty-two hours.

For those of us on #teampeirs, we knew that this action was important to Jack and his men, but we didn’t really grasp how important it was until we visited the village and did some additional research into the way in which this action was memorialized. In Peirs’s papers, he has a number of photographs of the war memorial in Le Verguier. Peirs attended the memorial dedication on Sunday, October 3, 1926. His photographs indicate that the dedication was well attended by veterans who proudly wore their medals and were joined their former general, Sir John Capper, in paying tribute to their fallen comrades.

General Sir John Capper dedicating the new church belfry on behalf of the veterans of the 24th Division who raised the funds for its construction.

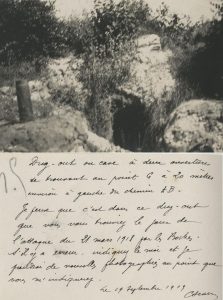

Our team visited the village this past summer. The scars of the war are no longer present; only the memorial church bell tower, the war village memorial, and a few soldiers’ graves are all that remains of the events of 1918. But in the immediate years after the war, the situation was vastly different. The landscape was in recovery and the town severely damaged. In 1919, Peirs wrote to the mayor of Le Verguier on at least one occasion, inquiring as to whether there were any graves of 8th Queen’s men in the area. He asked the mayor for photographs of the dugouts and trenches that still existed. The mayor wrote him back and enclosed annotated photos.

One of the photos in which the mayor sent to Peirs. This was believed to have been his command HQ during the battle.

As we have followed the story of Peirs, we have come to appreciate how this action – one major event in his three years at the front – in many ways defined his war service. Though Peirs would fight in the more successful 100 days campaign at the end of 1918, the hard-fought battle at Le Verguier – one in which he eventually ordered a retreat – was an action that he clearly saw as having significant meaning. Peirs had an ingrained sense of honor and the actions of his men that day demonstrated character traits – courage, determination, ingenuity, and skill – that he clearly valued.

Fittingly, when Peirs died in 1943 the former medical officer of his battalion – the man who ordered him to the rear with the baggage before the battle, C.J. Lodge Patch – penned a tribute to his commander under the headline ‘Peirs of Le Verguier’.

The doctor wrote of the place in which fate had placed Peirs and his men on the morning of the 21st, describing him as ‘a non-professional soldier who fought one of the greatest holding actions of the Great War.’ Bidding farewell to his commander he continued, ‘Good-bye, Peirs! Many an officer, man a man, have been waiting to welcome you these twenty-five years and more – all those, in fact, whose deeds are enshrined in that memorial at the little village of Le Verguier.’