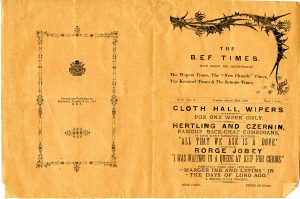

Occasionally, when #teampeirs rifles through the collection, something truly shocks us and makes us reevaluate everything we thought we knew about Jack Peirs. This was the case in December, when archivist Amy Lucadamo came across a poem written by Jack that was published in The B.E.F. Times, a trench newspaper that incorporated the most famous of these publications, The Wipers Times.

The stoic, sarcastic, and tight-lipped Jack we have come to know – who almost never revealed his true feelings in his letters home to his family – wrote poetry.

Well, he wrote one poem. That we know of.

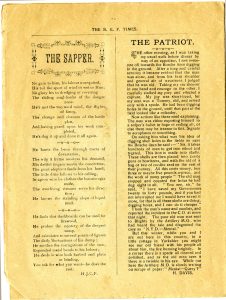

It was called “The Sapper,” and it was published one hundred years ago today on January 22, 1918.

We like to think of “The Sapper” as an ode. Much of what was published in trench newspapers dealt with the regular trials and tribulations of the First World War soldier, often in a comedic manner. The trench newspapers, after all, were published by soldiers, for soldiers. They wrote about things that mattered to them and that only they could understand. Perhaps this is why Jack felt comfortable publishing a bit of poetry in The B.E.F. Times – trench newspapers were about military matters, not excessive expressions of emotion.

Jack’s poem is rather transparent, which is helpful for those of us looking to analyze what he was trying to say. He titled his poem “The Sapper,” and the poem was, indeed, about a sapper. In the British Expeditionary Force during the First World War, a sapper was a kind of engineer. He served at the front and was responsible for repairing and building trenches and digging tunnels. He performed essential work and Jack, apparently, felt that the under-appreciated sapper deserved to be the subject of an ode.

Indeed, Jack begins his poem by noting that the sapper’s work was “unrequited.” There was “no glory” in the sapper’s work as he built and rebuilt “the sliding mud-banks of the danger zone.” When faced with “the change and chances of the battle plan / and having gazed upon his work completed” the sapper simply did his duty and “done it all again.” This first stanza of Jack’s poem is a tightly woven description of the sapper’s steadfastness amidst ever-changing battle plans and volatile weather. To Jack, the sapper was indispensable.

It is in the second stanza, though, that the admirable focus of the first stanza becomes rather lost amid quite a lot of mixed metaphors. Jack attempts to liken the sapper’s work to a brilliant, complicated musical composition (“his deftful fingers weave the concertina”), the animal kingdom (“the giant elephant feeds from his hand”), and a bit of classical artistry (“In apron wire he clothes the breastworks nude”). It is quite difficult to follow this section of the poem. Jack was clearly jumbling images together to imitate what he thought of as good poetry. He wasn’t entirely successful, although he did rein things in towards the end of the second stanza by writing of the sapper’s knowledge of “the standing slope of liquid mud.”

In the third and final stanza of Jack’s ode to the sapper, he manages to more successfully elevate the sapper’s work. He writes: “He soothes the corrugations of the iron / Expanded metal bands to his behest / He deals in wire both barbed and plain or binding…” Despite the odd shifts from past to present tense, Jack does a better a job in this stanza of describing the work of the sapper. He sticks to a more realistic depiction instead of relying on ill-fitting metaphors to create a noble image of the work. Jack finishes his ode with a final nod to the unsung, hardworking, and responsive hero of the trenches: “You ask for what you want–he does the rest.”

Thus ends Jack’s poetic debut.