Transcription

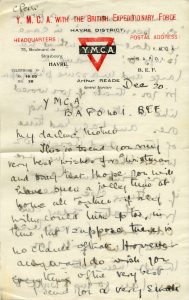

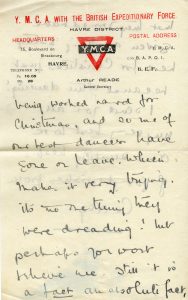

BAPO no. 1. B. E. F.

This is to send you my

very best wishes for Christmas

and say that I hope you will

have such a jolly time at

home all together, if only

Willy could turn up too, in

time, but I suppose there is

no chance of that. However

anyway I do wish you

everything of the very best.

I send you a very small

[page]

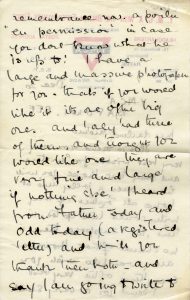

remembrance now, a poilu

“eu permission” in case

for Lord knows what he

is up to! I have a

large and massive photograph

for you – that’s if you would

like it. its one of the big

ones and I only had two

of them, and thought you

would like one. They are

very fine and large

if nothing else! I heard

from Father today and

Odd today (a registered

letter) and will you

thank them both – and

say I am going to write to

[page]

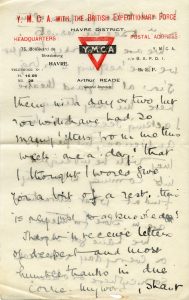

them in a day or two, but

you will have had so

many letters from me this

week one a day! that

I thought I would give

for a bit of a rest. This

is only just to acknowledge!

They will receive letters

of deepest and most

humble thanks in due

course. My word, shall

[page]

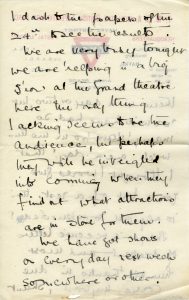

I dash to the papers of the

24th to see the results.

We are very busy tonight.

We are helping in a big

show at the grand theatre

here, the only thing

lacking seems to be the

audience, but perhaps

they will be inveigled

into coming when they

find out what attractions

are in store for them.

We have got shows

on every day next week

somewhere or other,

[page]

being worked hard for

Christmas, and some of

our best dancers have

gone on leave, which

makes it very trying.

it’s not the thing they

were dreading! but

perhaps you would

believe me. Still it is

a fact an absolute fact,

[page]

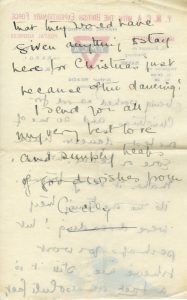

that they would have

given anything to stay

here for Christmas just

because of the dancing!

I send for all

my very best love

and simply heaps

of good wishes yours

Cecily.

Commentary

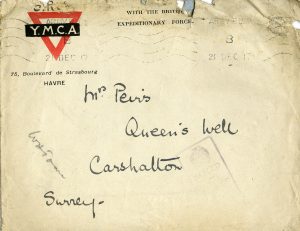

As Christmas 1917 drew near, Jack Peirs was preparing to spend the holiday at home in Carshalton for the first time since 1914. Since the beginning of December, he’d been at the Senior Officers’ School in Aldershot, and the close proximity allowed him to make regular visits to his family, heading home for dinners, avoiding bridge games, and finally meeting his goddaughter, who was born over the summer. But as the Peirs family prepared to welcome their only son home for the holidays, they undoubtedly missed the presence of their daughter Cecily.

he oldest of the four Peirs siblings, Cecily was a professionally trained singer who studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London. During the First World War, she volunteered with the Red Cross and YMCA, touring England and later France to perform in the variety shows and musicals intended to offer entertainment and benign distraction to soldiers at the front. As indicated by her stationery letterhead, Cecily was spending Christmas near Le Havre in Normandy, about 250 kilometers from the 8th Queens, who were in divisional reserve at Vraignes-en-Vermandois.

At face value, Cecily’s letter to her mother evokes a big personality. Her writing is full of intensifiers and superlatives, combined in an effusive style that seems oratory, as if the letter was written to be read aloud. Its author jumps rapidly from topic to topic, even though she’s writing “only just to acknowledge,” and she uses almost more exclamation points in one letter than her brother does in 271. Where he typically closes with “love to all,” she outdoes him tenfold, sending “for all my very best love and simply heaps of good wishes.” Visually, Cecily’s script sprawls broadly across the paper, and like Jack she seems to fit relatively few words on each page.

The reader of this letter is confronted with a deep and missing context. It is full of in-jokes and references, suggesting both a close relationship and a regular, nearly daily correspondence between mother and daughter. The collection at large provides a few clues: “Willy” is Gladys’s husband William, also on active service and away from Queen’s Well for the holidays, and we can gather from Cecily’s volunteering history that by December 1917 she was reasonably experienced in this kind of work. However, her letter fails to answer most of the questions it raises – what was the “small remembrance” she sent, and just what was the soldier she mentioned up to? Why was she dashing to the papers on the 24th, and what were the results she found there? And what was the thing the other YMCA volunteers seem to have been dreading? Perhaps more letters from Cecily would provide answers to these questions.

Regardless, this one helps us to draw a few conclusions. Cecily seems to have been dedicated to her work, enough so that she chose to remain in France for Christmas when she likely could have gotten leave if she had really wanted to. Like her brother, she is anxious to put on a good face in writing to her family, making the best out of a less than ideal situation as Jack does time and again. Her letter provides an example of how the war changed things for the Peirses, trading a brother for a sister, at least temporarily, as the conflict entered its fourth year.