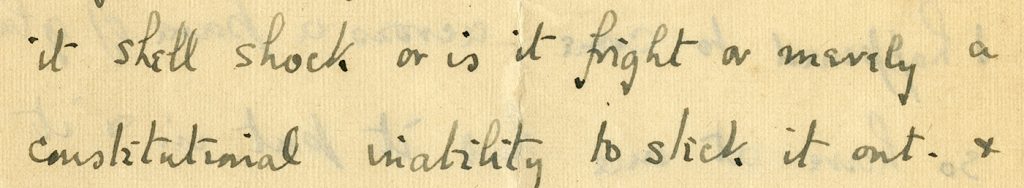

‘A constitutional inability to stick it out…’ [1]

Peirs rarely mentions the emotional effects of the war when he writes home to his family. It wasn’t in his character to talk about, or linger upon, his feelings. In fact, in this letter he appears to even mock a fellow soldier potentially suffering from shell shock. Peirs derides the soldier’s ‘constitutional inability to stick it out.’ What does he mean by ‘a constitutional inability’? What does this dismissive comment show us about the emotional expectations for men of his generation?

By 1916, shell shock was a diagnosed medical disorder, yet it remained something of an enigma. Peirs had undoubtedly seen men who broke under the strain of war. He had seen men traumatized and had participated in traumatic events.

Though we are apt to see Peirs’s words here as callous, they provide an avenue for historical context. Modern views of First World War is that lasting trauma was inevitable for soldiers, but there is history that pushes back against the idea of a universally traumatized soldier.

How did men like Peirs and millions of others survive the rigors of the front and carry on? In the case of Peirs, there are three major factors from his correspondence:

- pre-war education grounded in Edwardian masculine values

- emotional adaptation through experience of battle

- support from and connection to family

Education

The first aspect was Peirs’ masculine educational conditioning. As a member of the establishment class, Peirs attended both the public school Charterhouse and New College, Oxford. At school, through sport and discipline, Peirs learned the character traits of stoicism, endurance, self-control, and ‘suppression of sentiment,’ considered markers of the Edwardian soldier-hero.[2]

Young men like Peirs were taught to repress their own emotions, while learning ideals of heroism through emotional reticence. In Peirs’ 270 letters home from the war, these traits are regularly found. Duty and perseverance through hardship were foundational to his identity.

Emotional adaptation

Peirs’ first battle was at Loos and it was a disaster for the 8th Queen’s and the rest of the 24th division. Peirs’ men attacked German trenches without preparation or artillery support. Half the battalion was killed or wounded in about a half-hour. With their colonel among the dead, Peirs took command of the battalion. After Loos, he wrote his father the most emotional letter in the whole collection. Later, Peirs wrote to the British official historian Sir James Edmonds that he was traumatized by the experience at Loos:

“Personally I must plead to considerable mental disturbance in my first action. I had never had a bullet or shell fired anywhere near me before, and in my view he is an exceptional man who can control himself, much more his men, in such a situation. Apply this to practically every man in the brigade and an additional reason for failure becomes apparent. The men were quite right who said they would do better next time, and I have no doubt they did.”[3]

Despite this, he writes letters home within weeks of Loos about the fine weather, the A1 wine and beer in France. His combat performance after Loos indicates that he was effective in managing fear and adjusting to it. A 1917 evaluation mentioned his energy, drive, and “cheerful disposition.” Rather than being run-down through his service, Peirs got better at his job and more accustomed to life at the front.

Family – at the front and at home

Peirs enjoyed the company of the officer’s mess and in this letter, he wrote about finding a windowpane for it, a luxury. He liked fine drink, tobacco, and food – he arranged for hampers to be sent from some of the best stores in London. He read books and magazines. He organized field days and soccer matches for his men. He bought beer for them from Trappist monasteries, and organized films and concerts. He was not unlike a schoolmaster doting over his ‘lambs’, the word he used for the men under his charge.

His actual family also provided an incredible amount of emotional and material support. His parents and sisters wrote constantly and sent whatever Peirs requested and many things he did not. This November 21 letter to his sister Olive exemplifies the close, teasing relationship that he had with his three sisters. He is proud of the eldest, Cecily’s, achievement passing her exam at the Royal Academy of Music, but still gets in a few gibes. He even indulges in some local gossip.

Education, adaptability, and family – these things helped Peirs adjust to war. They provided him with models of masculine stoicism and emotional resilience during battle, but also support and continued connection to home for the quiet, waiting moments of the war. This balance between expectations and support seems to have worked well for Peirs allowing him to bounce back from trauma and excel in leadership. Unfortunately, as this letter indicates, he did not have patience for those who fell short of expectations or lacked the same resiliency that he developed.

[1] Commentary adapted from a conference paper delivered by Ian Isherwood at the Society for Military Historians annual meeting, May 2019.

[2] Michael Roper, ‘Between Manliness and Masculinity: The “War Generation” and the Psychology of Fear in Britain, 1914-1950’, Journal of British Studies 44:2 (April 2005), 347.

[3] CAB 45/120 HJCP to Sir James Edmonds, June 17, 1926.

Transcription

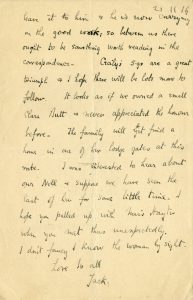

My dear Odd,

Many thanks for yours of the 15th. I was interested to hear you have our Geoffrey with you. I am prepared to bet a good deal that there is very little wrong with him. I wonder if he calls it shell shock or is it fright or merely a constitutional inability to stick it out. & those bally balloonists live in the lap of luxury & the gunners say that most of them are positively futile, when they might be a lot of use. I think most people regard them as contemptible except the few cases of those who have been wounded before or are over age etc. I shouldn’t say you are very like him in the face, as some people including himself think he is rather good looking (that should make you think a bit, my fair one). I will tell Joe when I see him. He is away at present on a course & enjoying himself hugely I understand. Anyhow he is not

[page]

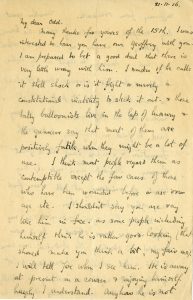

suffering from overwork. another quiet day, occupied in wandering round the trenches & putting a window in our mess, which only had a doorway to light us by before. I happened to come across a pane of glass so have at once had it put in & it makes all the difference. Glass is very hard to find in anything but bottle formation & a whole pane is a great luxury. Dug-outs ^owners as a rule if they boast of windows at all never find any glass to put in them. The C. O. has again returned, so my reign is once more closed. He is now occupied in strafing the Division over some of their usual folly. I occupied a lot of time last night in writing a suitably sarcastic note but eventually decided to

[page]

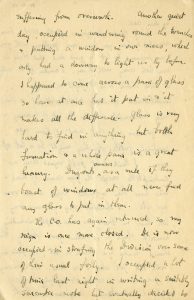

leave it to him & he is now carrying on the good work, so between us there ought to be something worth reading in the correspondence. Cecily’s 5.gs are a great triumph & I hope there will be lots more to follow. It looks as if we owned a small Clara Butt & never appreciated the honour before. The family will yet find a home in one of her lodge gates at this rate. I was interested to hear about our Nell & suppose we have seen the last of her for some little time. I hope you pulled up with Miss Hayter when you met thus unexpectedly. I don’t fancy I know the woman by sight.

Love to all