Like many archivists, I have found my traditional workflows thrown into a state of upheaval over the past few months. With physical collections materials inaccessible, I have refocused my attention from onsite projects to ones I can complete while working from home. While this process has had its challenges, it has also presented some opportunities – including the ability to return to one of my first duties (and first loves) as an archivist and historian: transcription.

I know my fondness for transcription isn’t necessarily popularly felt, and I agree that at times it can be a chore. Not every project is as pleasant as the Peirs letters; not every correspondent writes in Jack’s neat Charterhouse hand, and not every letter is still laugh-out-loud funny a full century later. Despite its imperfections, lately I’ve found transcribing to be a low-impact way to feel somewhat productive. I enjoy the process not only because I get to make and follow a set of rules, but also because I am actively working to understand and clarify information set down by someone from the past. In short it is one of the parts of the research process during which I feel the closest to the history.

Recently I have been participating in a few different crowdsourced transcription initiatives. As always, the Smithsonian Transcription Center offers a plethora of incredible collections and tools to work with (read more about the Freedman’s Bureau papers on our Instagram page). Working on these projects is very rewarding, but reading script can be tough and many of the records have multiple creators, meaning it’s not a simple matter of getting to know a single hand. To add some variety, and to help move along my own research, I have also focused on transcription of newspaper articles, or more accurately correction of transcriptions obtained through Optical Character Recognition.

So far, I’ve primarily worked with First-World-War era-articles about the 8th Battalion, The Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment, available through the British Newspaper Archive (The National Library of Australia’s Trove database is another great resource). As my goal is to find out more information about the men of the 8th Queen’s, my process has involved searching or browsing Surrey papers for relevant articles, then comparing the computer-generated OCR text to the image of the scanned page and making any necessary corrections.

While making text corrections is generally pretty easy, I have encountered some unexpected difficulties in actually identifying the articles that I want to read and correct in the first place. OCR does its best, but it’s not perfect. It is a computer program after all, and its accuracy depends on the quality of a scan of century-old newsprint, so I have learned to keep my expectations low. As I grow more familiar with OCR, I have noticed some patterns in how it functions and come up with some searching strategies for working around its temperamental nature.

At first, I approached searching for content on the British Newspaper Archive as I would any collections catalog: through the Advanced Search function and Refine Search limiters. I began with a search for a surname such as Cantillon or Cressy and limited my results to the appropriate geographic region and date range. These searches returned some of the types of articles I was looking for, but I knew there had to be more. I tried many of the tricks that usually work when searching academic databases or library catalogs, including phrasing and spelling variations, creative use of limiters, and every configuration of Boolean operators I could think of – all to no avail. Although I was trying to narrow my searches, they continued to return greater numbers of results, with less relevance.

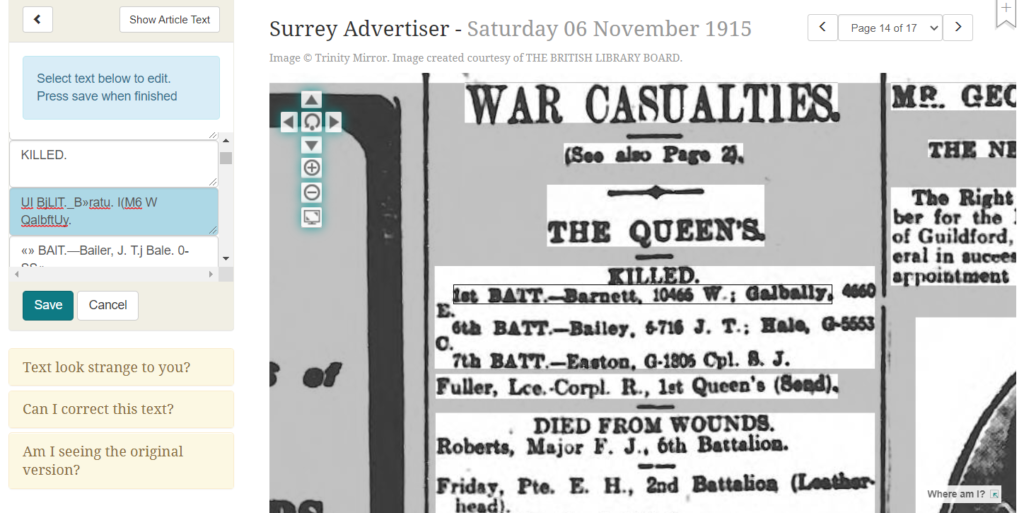

It took correcting the same OCR errors over and over again to realize that there were unknown, unidentifiable variables that I couldn’t fully search around: the OCR errors themselves. Certain printed characters habitually returned as different plaintext characters: F became P, s became *, and h became li. Articles about the East Surreys were accompanied by OCR transcriptions that referred to the Fast Surreys, and our own Colonel F. H. Fairtlough became P. H. Fairclough.

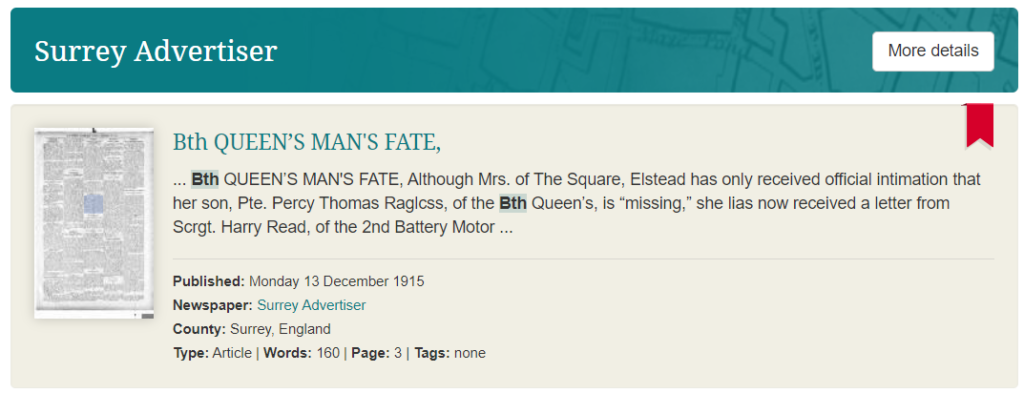

When I did hit upon an article that mentioned the 8th Battalion, without fail I had to correct the corresponding OCR text which read Bth Battalion. It took me an embarrassingly long time to make the connection between what at first seemed like two disparate points. When I ran a search, I wasn’t searching the contents of the articles themselves – I was searching the OCR transcriptions of the articles. In order to find what I was looking for, I needed to alter my search terms accordingly. I ran a search for Bth Battalion under the proper parameters, and my results improved dramatically.

There were, however, other factors to take into consideration: the syntax and grammar of different papers, and how these were interpreted by the OCR. For example, papers sometimes printed soldiers’ given names, sometimes initials, and sometimes a mix (e. g. Hugh Peirs, H.J. Peirs, H.J.C Peirs). Abbreviations of ranks (Lance Corporal, Lce.-Cpl., Lce.-Corpl.,), and variants in phrasing (8th Battalion, 8th Battn., 8th R.W.S.) further complicated things. Throw in the absence or presence of spaces between characters, special characters, and hyphenated last names that are typical of many British officers – plus OCR errors – and you have a recipe for disaster, or at least significant frustration.

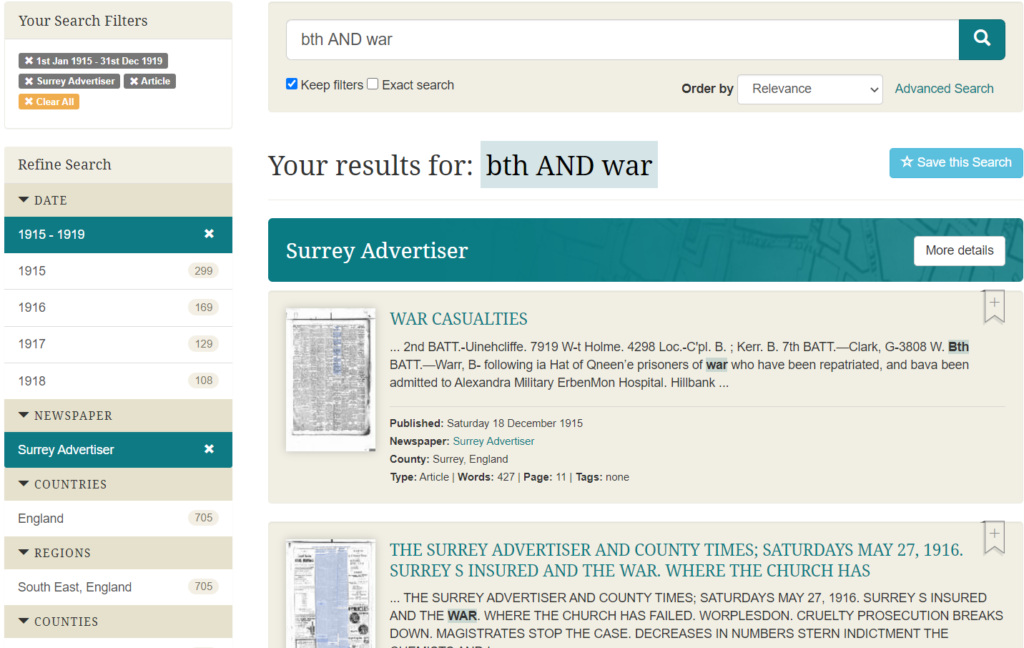

So what is the intrepid researcher to do? In my case, run a search for Bth AND war across all issues of the Surrey Advertiser (Jack’s preferred paper and the one with the most promising content) between 1915 and 1919. There are fewer results than one might think, and by cross-referencing dates with times at which we know the Queen’s saw action, gradually the cream rises to the top. This method has so far been the most successful in helping me to find the articles that are helpful to my research and correct the accompanying transcriptions.

As I’ve continued with this disorganized little project, I’ve come across published letters, death notices, obituaries, casualty lists, descriptions of battle, and much more written about and by the men of the 8th Queen’s. I have also encountered the same kind of content related to other regiments and battalions. In theory the whole point of my search is to identify and make more accessible the records about the men that Peirs led, those whom he served and fought with. Truthfully I find it difficult not to try to do the same for others as well. The stories of the 5th Queen’s in India or the 9th Surreys on the Western Front are just as important as those of the men whose names are more familiar to us. Correcting the spellings on one casualty list for a regiment of the City of London Rifles or the Royal Fusiliers might help some other researcher find what they are looking for. If not, it is at the very least a small act of remembrance.