The Peirs letters, photographs, documents, and artifacts make up a vast collection. Not vast in cubic feet, as archivists measure, but vast in temporal and subject coverage. According to historian Dan Todman, the First World War is where history begins for many British families, because the artifacts and stories from their ancestors come from just outside of modern memory. Families might have a photo or a few letters, but not “vast collections of letters, photographs or meticulously recorded myths on which to draw.”[1] And while Peirs did not live long enough to pass his story onto his grandson, the letters themselves are a tangible connection with the past. As described by historian Paul Cornish they “embody the real and imagined worlds of wartime and post-war experience.”[2]

Within Jack’s papers are letters from the Imperial War Museum. In 1919 the fledgling institution was looking for “records of all the uniforms and equipment worn during the recent war.” The museum valued authenticity and provenance in its collecting scope. It was most interested in artifacts that showed signs of use and battle damage. Connection to an individual, location, or battle and “scars of honour”[3] created a more authentic experience for the visitor.[4]

The Peirs letters are tangible connections to the trenches, but he wrote them as a common cultural practice, not for posterity. They are chatty and conversational with varied topics. There are few moments of reflection or noted awareness of the historical moment. With over 200 letters their “everydayness” is easy to see. It surprises students that Jack focused on the little things. He often wrote about creature comforts, reading material, and housing. His role as the creator of this collection was simple. He wrote home to chat with his family through a tumultuous time. His family’s role was to save the letters, adding a layer of meaning and importance to them. There is evidence that during the war his parents shared Jack’s letters with his sisters, providing a touch point for each of them. When the letters were later all gathered together another layer of meaning was created – the letters as a record of war experience. When they were left to later generations, who did not know Jack, they took on the role of historical record – primary sources of a historic event.[5]

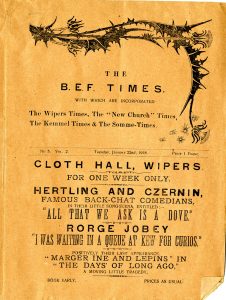

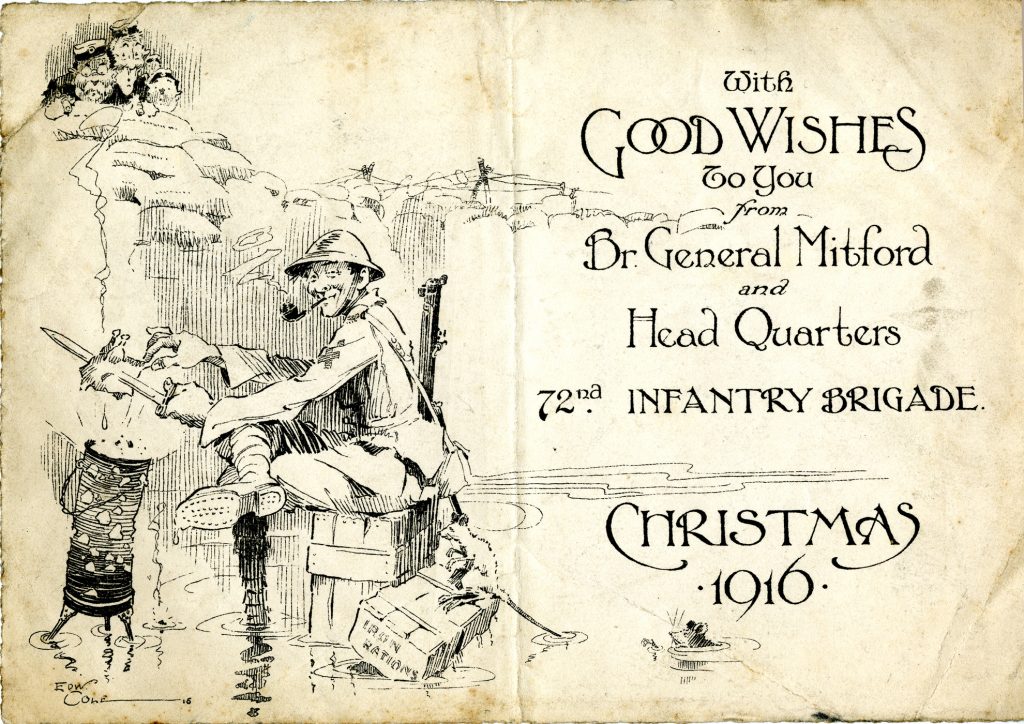

The artifacts left from Jack’s war experience, though few in number, do tell us something about him and about his consideration of his own experience. The things that he kept are unique to him and to his battalion. They include Christmas and New Year’s dinner programs signed by other officers, a copy of the B.E.F. Times containing a poem Jack wrote after two and a half years in the trenches, and maps he carried in his pockets. These are personal items, but not intimate ones.

This collection does not include belongings often present among other wartime manuscripts collections. There are no day-to-day items like pens or pencils, blank stationary or notebooks, Bible or other reading material, cigar boxes, a comb, razor, mirror.[6] Their absence gives the impression that when he arrived home, Jack did not carefully pack away his things from the war. It is incongruous with someone who seemed so proud of his service and who excelled in a military role. The impression that it did not take long for Jack to move on from his wartime experience, is not the only explanation. Perhaps he continued to use some of his things, some were lost in battle, and there were, very likely, things he discarded for better quality versions once home.

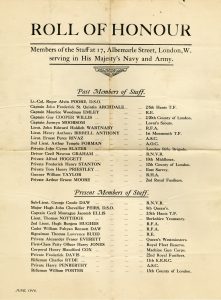

June 1916 listing of staff members from 17 Albemarle Street, London (the address of Jack’s solicitors firm) who were serving in the Navy or Army.

#TeamPeirs has discussed how much Jack seemed to take the war in stride. We have come to think of it as the war being something that happened to Jack, but not the defining moment of his life. He was living at home when the war began and working in the same profession as his father at the same solicitors’ firm. Although not the eldest child, he was the only son. Being a soldier was an opportunity for Jack to establish a role in his family that only he could play. He was not passive in his experience as a soldier. His military service began before the first shots were fired and he succeeded when given the opportunity to lead.

Jack may have compartmentalized his war experience, but it was woven into the rest of his life. After the war, he went back to the roles of son and solicitor, marrying in 1922, but he had a new role as veteran. He kept up with memorial activities and reunion groups. His post-war activities are something that our team is currently researching. He preserved artifacts that connected him to other officers and the commemoration of the 24th Division. These tokens of membership and identity are part of the legacy that Jack carried with him from the trenches.

[1] Dan Todman, The Great War in Myth and Memory (Bloomsbury: London: 2007), 214-215.

[2] Paul Cornish, “‘Sacred Relics’ Objects in the Imperial War Museum 1917-39” in Matters of Conflict: Material Culture, Memory and the First World War edited by Nicholas J. Saunders (Routledge: London, 2004), 41, ProQuest Ebook Central.

[3] Charles ffoulkes, the first Curator and Secretary of the Imperial War Museum, as quoted by Alys Cundy, “Objects of war: the response of the Imperial War Museum, London, to the First and Second World Wars” Post-Medieval Archaeology 51, no. 2 (2017): 264, https://doi.org/10.1080/00794236.2017.1358989.

[4] Cundy, 263-265.

[5] Saunders, 6.

[6] Unfortunately, Jack’s uniform was destroyed after his death by extensive moth damage. Signs if his rank: service ribbons, pips, and epaulettes were kept safe, evidence of his family’s regard for his military achievements.