Transcription

8th Queens

B. E. F.

23. 8. 1916.

My dear Mother,

Many thanks to you for various letters & papers, a box of cigars, socks, copies of Gs letters. I have no news I can tell you. We have been in a small show & are now out of the line again with the prospect of a little rest, which we’ve not had lately. I got hit by a bit of a shell the other day on my right forearm, but it only bruised my arm & I didn’t notice it 5 minutes afterwards. However I may appear in the list as a wounded hero, so don’t worry if you see my name. I don’t know why they are going to put it in but it looks well. I am writing to the bank to send Father a cheque for the footballs, which have not yet arrived, but will probably come to-day or to morrow.

Love to all

Jack.

Commentary

Jack Peirs told his family very little about the Somme. In fact, the Peirs family was getting more from British papers than they were from their son at the front. In part, this was because Peirs was very busy with his work as adjutant of the battalion, but it was also for security reasons since he was in an active combat zone. So when he wrote his mother in his August 23rd letter ‘I have no news to tell you’ the emphasis should be on the words ‘I can tell you.’

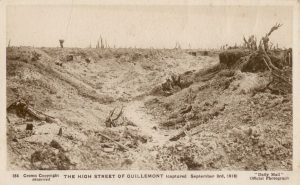

In fact, Peirs did have news. Two days before Peirs sat down to write this letter he was in a major fight. On 21 August 1916 the 8th Queen’s attacked along the Trones Wood/Guillemont Road, a battle that led to ninety-six casualties including seven officers wounded, Peirs being one of them.

What did the attack look like? According to the operational orders, the day opened with a preliminary bombardment of the German positions opposite. Later in the day, the infantry attacked. At 4:30 PM, Peirs and his men came out of their assault trenches and advanced behind a creeping barrage, fighting their way forward with small arms and grenades. At nightfall after taking a few enemy positions, the whole line was pulled back to their original starting point, their situation untenable. On the 22nd, the 8th Queen’s regrouped and licked their wounds.

In this attack Peirs was lightly wounded in the arm by a shell fragment. In his letter home he minimized the wound (and the attack) to reassure his mother that he was, indeed, okay and so that she will not worry about him. ‘However I may appear in the list as a wounded hero, so don’t worry if you see my name,’ is quite telling in this regard. Peirs was both downplaying the wound, but also the image of him as a ‘wounded hero’, which speaks to his anti-sentimentalism.

If you would like an interesting comparison, have a look at Peirs’s letter right after his first battle at Loos and then look again at this letter. Two battles fought eleven months apart and very different letters written home to his family. These letters show something of a change in Peirs over the year 1915-1916.