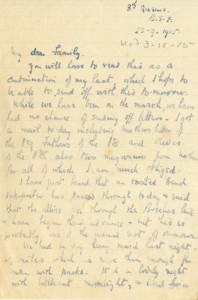

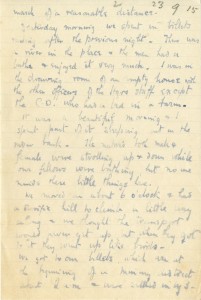

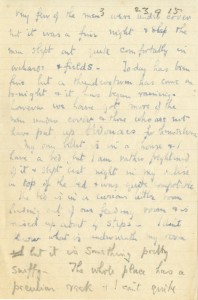

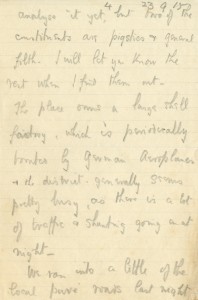

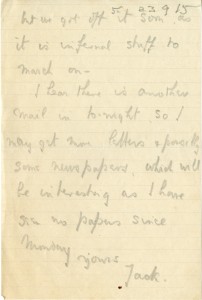

Transcription

8th Queens

B.E.F.

23.9.1915

(Rec’d 3 10-15)

My dear Family.

You will have to read this as a continuation of my last, which I hope to be able to send off with this to-morrow. While we have been on the march, we have had no chance of sending off letters. I got a mail to-day including mothers letter of the 19 fathers of the 18 and Olives of the 18 also two magazines from mother for all of which I am much obliged.

I have just heard that an excited French interpreter has passed through to-day & said that the allies are through the Bosches line and have begun their advance – but this is probably one of the usual sort of rumour.

We had a very heavy march last night 19 miles which is more than enough for men with packs. It is a lovely night with brilliant moonlight, & ideal for a march of reasonable distance.

Yesterday morning we spent in billets resting after the previous night. There was a river in the place & the men had a bath & enjoyed it very much. I was in the drawing room of an empty house with the other officers of the Hqrs staff except the C.O. who had a bed in a farm.

It was a beautiful morning & I spent part of it sleeping out on the river bank. The native’s both male & female were strolling up & down while our fellows were bathing but no one minds these little things here.

We moved on about 6 o’clock & had a terrific hill to climb a little way along & we thought the transport would never get up but when they got to it they went up like birds. We got to our billets which are at the beginning of a mining district about 2 a m & were settled in by 3. Very few of the men were under cover but it was a fine night and the men slept out quite comfortably in orchards & fields. To-day has been fine but a thunderstorm has come on to-night and it has begun raining. However we have got more of the men under cover & those who are not have put up bivouacs for themselves.

My own billet is in a house & I have a bed but I am rather frightened of it & slept last night in my valise on top of the bed & was quite comfortable.

The bed is in a curious little room leading out of our feeding room and is raised up about by steps. I don’t know what is underneath my room but it is something pretty sniffy. The whole place has a peculiar reek and I can’t quite analyse it yet but two of the constituents are pigsties and general filth. I will let you know the rest when I find them out.

The place owns a large shell factory, which is periodically bombed by German aeroplanes & the distinct generally seems pretty busy, as there is a bit of traffic & shouting going on at night.

We ran into a little of the local pavé road last night but we got off it soon, as it is infernal stuff to march on.

I hear there is another mail in to-night so I may get more letters and possibly some newspapers, which will be interesting as I have seen no papers since Monday.

Yours

Jack.

Commentary

In his last letter, Peirs indicated that his battalion was readying to move towards the front. Shortly after he composed it on the 21st, the men marched for three hours in the fading light, reaching their billets at 11:30 PM. On September 22, the 8th Queen’s bathed in a mill stream before setting out at 6:00 PM on a night march of 19 miles reaching Berguette in the early morning hours of the 23rd.

The 8th Queen’s had been trained extensively before departing for France. Upon arrival, they continued their training, specifically their tactical education under the direction of more specialized staff officers. As Peirs indicates in this letter, the men were fit enough to march 19 miles with heavy packs – they had trained to do so for over a year – though the march was likely exhausting.

What did the march look and feel like? Peirs indicates ideal walking conditions and ‘brilliant moonlight’, which likely helped the footsore men stay focused on the road ahead of them. But marching was still difficult on the bodies of soldiers, even those trained extensively.

British battalions were trained to march three miles in fifty minutes. The remaining ten minutes of the hour were devoted to rest. When ordered to halt, men would loosen their packs, smoke, urinate, and perhaps beyond anything else, banter and grouse with each other, complaining a central part of the formation of soldier camaraderie both then and now. After ten minutes, men would be shepherded/dressed back into line by their NCOs and would march onwards.

Here’s a photo of a battalion on the march in 1915. You can see the way that men have adjusted to their kit, hats to the side (or taken off), rifles carried in any number of ways, top buttons unfastened, yet the men were still dressed in column and keeping fine step with each other. Maintaining such order when exhausted, hungry, and thirsty is a testament to military discipline and the ability of soldiers to (somewhat reluctantly) adapt to it.

Within minutes of marching, the battalion would have been covered in dust from the road, men sweating through their flannel undershirts (and wool undershorts) and steaming in their heavy wool tunics, the webbing causing chafing and minor bruising as it adjusted on their bodies. Men kept focus by keeping their eyes on the man in front of them. Officers and NCO’s carefully watched each platoon for straggling or for men drinking without permission; and after nearly a year of training, the men of the 8th Queen’s no doubt understood that they were subject to military discipline.

Each soldier carried a heavy but not unmanageable burden. Standard kit consisted of a uniform (underclothes, wool outer-clothes, greatcoat, boots, puttees, cap, etc), webbing and pack to hold their gear, Short Magazine Lee-Enfield rifle, ammunition, entrenching tool, bayonet, ration, mess kit, personal items (socks, housewife, book, stationary, tobacco, etc), gas mask, and a quart of water. Here’s what all of this stuff looked like when laid out. One imagines that the men of the 8th Queen’s after 19 miles of marching (over six hours) would have had very sore feet and shoulders, dirty faces, dusty uniforms, and dry mouths. No doubt the bath and rest day they had on the 23rd was much needed.

For books on the lives of WWI soldiers, see Denis Winter’s Death’s Men and Richard Holmes’s Tommy.