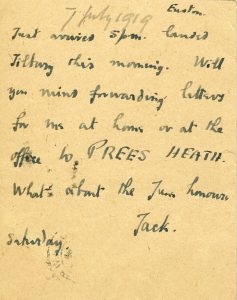

Euston.

(7 July 1919)

Just arrived 5 p. m. landed

Tilbury this morning. Will

you mind forwarding letters

for me at home or at the

office to PREES HEATH.

What about the June honours

Jack.

Saturday.

Commentary

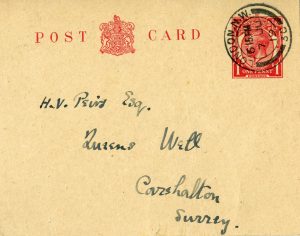

In Jack’s words, “so that’s that.” This short postcard is the final item in the Peirs collection penned by Jack. As indicated in the brief note to his father, Jack progressed first to Prees Heath Camp and eventually made his way on to Mansfield, where the 8th Queens Service Battalion was formally demobilized following its service in the First World War.

As we’ve discussed previously, and just as the story of the First World War did not end on 11 November 1918, Peirs’s story did not end on 7 July 1919. He went on to marry, raise a daughter, continue in a moderately successful career as a solicitor, and serve in the Home Guard during the Second World War. The honors he earned during his time in the military bolstered his social status in later years, but Jack seems to have kept his own reflections on the war largely private. When he did outwardly engage in commemoration, it was with a focus on remembering those who were lost and fostering a sense of community among veterans.

On Sunday, October 3, 1926, Peirs and other members of the 8th Queens returned to Le Verguier, France, with their former general, Sir John Capper, to pay tribute to those who fell in their 1918 defense of the village. Along with his father, Hugh Vaughan Peirs, Jack took an active role in the planning and construction of a war memorial in his hometown of Carshalton, and as early as January 1919 was expressing hopes of helping to organize “a club for all men who have served the country in an active capacity in the war.” Such a club would “retain the Espirit de Corps of the army & be of infinite benefit to the nation.” When Peirs died in 1943, he was remembered by a fellow officer as “a non-professional soldier who fought one of the greatest holding actions of the Great War.”

With the publication of this final letter in the collection, our project achieves its original goals: to make Jack’s letters available to the largest number of people possible and to provide a learning opportunity for students. Other documents by, about, and related to Peirs are found in various manuscript collections at repositories including the Imperial War Museum Archives and the National Archives of the UK. However, the letters published here represent the greatest part of Jack’s surviving wartime correspondence.

This collection, compiled and retained by Peirs’s relatives and labelled by his wife Eirene as “interesting for posterity,” is made available by the extraordinary commitment of the Dracopoli/Zorich family. I believe I speak for the entire project staff in simply saying that words are not sufficient to express our gratitude to them. Speaking for myself, my personal gratitude to every member of the staff, past and present, is equally as inexpressible.

The lieutenant colonel who scribbled the above note to his father upon his return to England on 7 July 1919 was a different man from the major who had penned a careful account of his first few days in France for his mother on 14 September 1915. Jack’s story is one of military heroism, personal growth, true leadership, and profound honor. It is also one of deep contradiction, inestimable loss, serious doubt, and incomprehensible tragedy. Peirs’s wartime experience was not just his own, but undeniably shared, inextricably tied to the experiences of each member of the 8th Queen’s.

As a team we have had many occasions for reflection, and I think we will have many more. Today, like every day, represents another opportunity for remembrance.

Jenna Fleming ’16

What a wonderful thing you all did!!