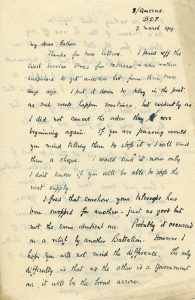

8/Queens

B. E. F.

7. March 1919.

My dear Father,

Thanks for two letters. I paid off the

Civil Service Stores for tobacco & was rather

surprised to get another lot from them two

days ago. I put it down to delay in the post,

as such events happen sometimes, but evidently as

I did not cancel the order they [illegible] are

beginning again. If you are passing would

you mind telling them to stop it & I will send

them a cheque. I would send it now only

I don’t know if you will be able to stop the

next supply.

I find that somehow your telescope has

been swopped for another — just as good but

not the same identical one. Probably it occurred

on a relief by another Battalion. However I

hope you will not mind the difference. The only

difficulty is that as the other is a Government

one, it will be the broad arrow.

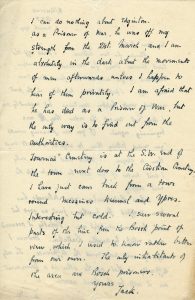

[page]

I can do nothing about Edginton.

As a Prisoner of War, he was off my

strength from the 21st. March, and I am

absolutely in the dark about the movements

of men afterwards unless I happen to

hear of them privately. I am afraid that

he has died as a Prisoner of War, but

the only way is to find out from the

authorities.

Tournai Cemetery is at the S. W. end of

the town next door to the Civilian Cemetery.

I have just come back from a tour

round Messines Kennel and Ypres.

Interesting but cold. I saw several

parts of the line from the Bosch point of

view, which I used to know rather better

from our own. The only inhabitants of

the area are Bosch prisoners.

Yours

Jack.

In reading this letter, one may be confused by Peirs’s mention of “Edginton.” Family members of men in the 8th Queen’s occasionally asked his parents to write to their son in an effort to find out what had become of their loved ones. In this letter, Peirs tells his father that he is unsure of what happened to Edginton, but speculated that he had died as a Prisoner of War. Over the past week, we have looked into what might have happened to Edington after 21 March 1918.

On the morning of 21 March 1918, Peirs and the 8th Queen’s fighting in defense of Le Verguier at the opening of the German Spring Offensive. Though the 8th Queen’s was commended as a battalion for their efforts, they suffered terrible casualties. Those casualties included the loss of A Company at the remote forward outpost of Shepherd’s Copse. Edgington was in A Company and Peirs did not know his fate because he arrived up the line in Le Verguier after Edginton had already been captured on the morning of the 21st. The confusion of the battle meant that Peirs had little understanding of the German attack beyond what he witnessed and that he only pieced together a narrative from sources afterwards.

Private Edwin Cyril Edginton (page 35), an Assistant Clerk with the Education Board in civilian life, died in a hospital in Antwerp on 22 October 1918 only 20 days before the Armistice. He was 20 years old. Edginton is buried at Schoonselhof Cemetery in Belgium, and was brought to the cemetery in a post-Armistice relocation. Schoonselhof Cemetery contains 101 Commonwealth burials of the First World War, as well as 1,455 Second World War burials.

Though Peirs writes about Edginton’s capture with a lack of emotion, this letter and our search for Edington can serve as a reminder to historians that, though we are studying events that seem so far behind us, the people we are studying are more than just names in a letter or in a fallen soldiers list. They were real people with real lives and families who cared about them– families who often desperately searched for answers that they would never find. Though we are unsure of whether or not Edginton’s family members ever found his grave, Team Peirs is glad that we were able to find it for ourselves and share the information with all of you.